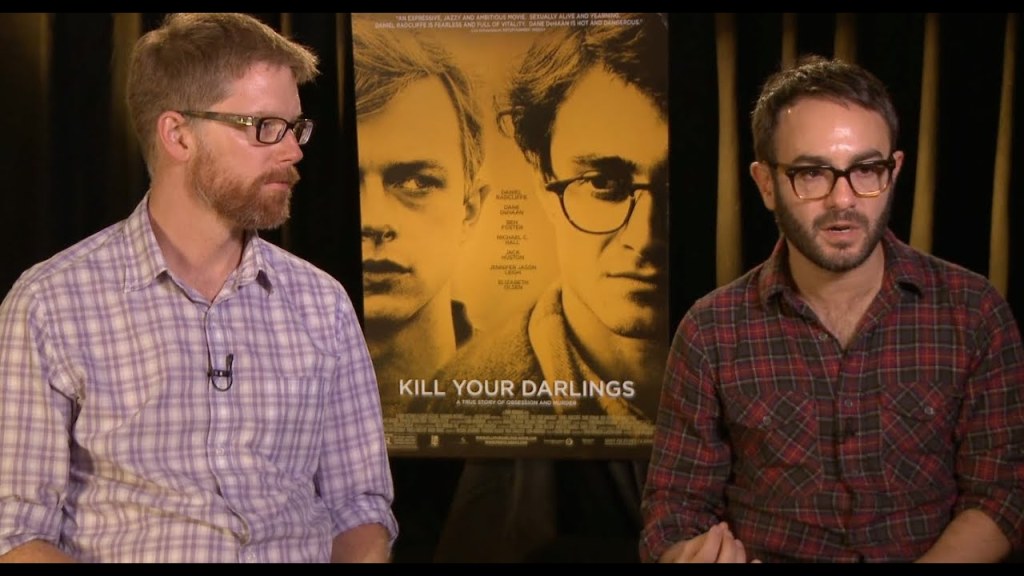

John Krokidas and Austin Bunn Discuss ‘Kill Your Darlings’

WRITER’S NOTE: This interview took place back in 2013.

John Krokidas makes his feature film directorial debut with “Kill Your Darlings” which stars Daniel Radcliffe, Dane DeHaan and Michael C. Hall. The movie is about a murder that occurred in 1944 which brought three poets of the beat generation (Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs) together for the first time. Radcliffe portrays Ginsberg as a 17-year-old who is about to start college at Columbia University, and he ends up falling under the extroverted spell of fellow classmate Lucien Carr (DeHaan) who introduces him to the poets who would later bring a new vision to writers everywhere. It is when Carr murders his love David Kammerer (Hall) that their relationship starts to become unglued.

Krokidas co-wrote the script for “Kill Your Darlings” with his Yale University roommate Austin Bunn. A former magazine journalist, fiction writer and reporter, Bunn graduated from Yale and went on to get his master’s degree at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. As for Krokidas, he later attended New York University’s Graduate Film Program where he made the short films “Shame No More” and “Slo-Mo.”

I got to hear how Krokidas and Bunn made the film under challenging circumstances when they appeared at the “Kill Your Darlings” press conference held at the Four Seasons Hotel in Los Angeles, California.

Question: What was the division of creative responsibility between you two like?

Austin Bunn: Probably like a lot of people in this room, I discovered the beats in college. I used to go to the campus bookstore and just track down the poetry collection, find Allen’s books and read them like they were some secret transmissions from the future version of myself. I was a closeted, young creative writer from New Jersey so Allen Ginsberg’s work meant the world to me. So, I had this really strong connection with Allen and of beat biographies and the history. I read a lot of the back catalog and I had come to John with the idea. So, in terms of the division of responsibility, I would write the first draft and then John would come in. The thing about John, as you will soon learn, he wanted to raise the emotional decibel level in every scene. John is one of the most riveting and vital and least hagiographic version of this story. We didn’t want to take the beats’ greatness as a given, so John sort of demanded that we write a really emotional roller coaster. Then we just went back and forth. John talks about it as the Postal Service, like the band version of producing a script. We were living in different cities at the time; I was at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop as a graduate student and John was in New York finishing film school.

John Krokidas: Austin wanted to do this as a play first. He was a playwright and a short story writer of some renown, and we were college roommates and we shared ideas with each other as college roommates and good friends do. But I, of course, started seeing the movie version in the back of my head and I had just gotten out of NYU film school and started convincing him that the play would be really flat and undramatic, but as a movie…

Austin Bunn: The Jedi mind trick!

John Krokidas: This would be amazing. But I would say I’m the structure guy I think, coming from NYU’s film program. I’m very traditionalist in terms of Sidney Lumet’s “find your spine,” and Austin is really wonderful with character and dialogue. If anything, he’s on a religious crusade against expository dialogue, and I would write these three paragraph monologues for each character expressing their emotion like that scene where Jennifer Jason Leigh finally turns to Allen to give him advice. I had a two-page monologue version and Austin crossed it all out (Austin laughs) and wrote the one line that’s in the movie, “The most important thing your father ever did was fail me,” which said everything.

Question: The movie is also very visual too because of the beats’ energy and such. How did you go about creating the look with cinematographer Reed Morano?

John Krokidas: I’m so proud of what we brought to this film. The movie is set in 1944 and it’s a murder story. Even in the writing process, I looked up and saw that “Double Indemnity” won Best Picture that year, and it was the year of “Laura” and “Gilda” and all these great American Film noirs. So, I said, “Why don’t we incorporate this even in just the fabric of the movie and start with the jail scene in a place of heightened tension flashback to more innocent times, and then build again to see whether or not these characters can escape or not escape their fate?” So, I started looking at noir style at first, but I thought an academic recreation of Film noir, who wants to see that? Going back to spine and theme, I thought what this piece was really about was young people finding their voice. So, what about going from conformity, the row houses of New Jersey and the pillars of Columbia, to nonconformity? And of course, where film noir went in the hands of the French was the New Wave. So I thought, “Okay well let’s start off with these controlled, composed, expressionistic-lit shots, and then as the boys go down the rabbit hole together, let’s take the camera off the tripod. Let’s get some jazzier free-form style.” So, I made this book of the 1940s. I had learned that Ang Lee, for “The Ice Storm,” did a 50 page book on the 1970s with colors, fonts and important historical events, you name it. So, I did that with the 1940s and then gave it to Reed. The great thing that I have learned on this is you can do all the academic treatises you want, but then you hire great people. She saw the goal post of what I wanted and then she showed me Jean-Pierre Melville’s films. She showed me films that meant a lot to her and then let kind of what I wanted filter through her own imagination. What I am amazed by specifically in her work is we did this movie in 24 days. Each scene was done in two hours or less, and she has the instincts to be like a documentary camera person and is able to light like that at the same time. We wanted to make sure this film felt relevant and contemporary as opposed to just being a traditional biopic.

Austin Bunn: (We didn’t want it to be) the greatest hits version of their lives.

John Krokidas: It was looking at Ryan McGinley photographs and contemporary, counterculture, young images of today and then finding what connected them to the 1940s. What was resonant in counterculture then and today at the same time.

Question: What was the direction that you were giving your actors? We were told that sometimes you would pull them aside for a more dramatic scene, but was there a consciousness you went into to direct the film and the actors? Were they any kind of specific kind of notes you gave them?

John Krokidas: Here’s the embarrassing story; Austin and I actually met freshman year because we were both acting in a production at Yale of “The Lion in Winter.”

Austin Bunn: Yes.

John Krokidas: Neither of us were the greatest actors in the world which is, I think, why we went into writing and directing. But I trained as an actor as an undergraduate and what you learn is that each actor has their own method and way. It’s whatever it takes for them to get the emotions to the surface. So, when I met with each actor that I cast, I would just simply ask them, “Have you trained? How do you like to work and what don’t you like?” Michael C. Hall gave me one of the greatest lessons in directing in which he said, “If what I am doing is not making you happy, don’t tell me that because that will make me self-conscious and it will make me think about what I’m doing. Just tell me to add whatever you want to what I’m doing.” That’s just a great lesson for life. Dan and I, when we were working together, we spent time before production (he was so generous and hard working on this) and he wanted to approach this like it was his first film which was very poignant to me. I said, “Would you like to try learning a new method and approach acting in a different style?” He said, “Absolutely!” So, with Dan, he’s so bright and in his head, and for the intellectuals Meisner works really well in focusing your action on what you are trying to do in the scene. Dane had trained extensively, and what he does is create a Bible for the character and does tons of research before production. Then he burns it and starts really becoming the character on set. Ben Foster (who plays William Burroughs) has something I’ve never seen another actor do which is, once we’ve basically got the scene up on its feet, he goes and he does the blocking of the scene by himself in the location several times. He calls it “the dance” because once he’s memorized the dance and knows the physicality (“I need to pick up the fork here, I need to put it down there”), he doesn’t have to think about it anymore and that’s completely freeing to him. So it’s like cooking this huge seven course meal where you have to get everything done at exactly the right time, but every plate needs a little bit of love in a different way. To me the greatest thing was being able to get this dream cast and then just to work with them to find how they like to work and what got the best out of them.

Austin Bunn: John had a really intuitive idea which was to keep the actors from reading past this point in the biographies, so none of the actors came in burdened by the mythology of who these guys would become. They were just 19-year-old kids. So, I think that was really smart and it released the actors from having to play the later decisions in their lives and the kinds of writers they would become. They just got to be young people, and that was a great relief I think for them.

John Krokidas: Yeah, and for us too as writers. I had a talk with Jack Huston once when he and I shared the same room and I’m saying, “Oh my god, I’m directing you as Jack Kerouac.” But we were like, “No. You are Jack who is a college student on a football scholarship who hates the other jocks, who just wrote a book which he thinks might be completely trite and he just wants to get out of college and have some real-life experience and join the war so he could begin to have real material to write his next book. That’s who you are.” That just liberated all of us.

Question: When writing the script, how much are you tied to the truth and how much are you allowed to take creative license?

John Krokidas: We did so much research for this. We felt we had to, and I think part of it’s our academic background because there’s so much in the biographies. There are so many biographies of them out there, but then also we would find different accounts online for example from David Kammerer’s friends. They said that that relationship between him and Lucien was never portrayed accurately and that Lucien actually kept coming back to David and David was asking him to end the relationship. And then we may have broken into Jack Kerouac’s college apartment together. We did the trick of pressing all the buzzers and then somebody let us in. But what’s interesting is Columbia students were living there and they had no idea that they were in Jack Kerouac’s apartment. So, we physically went to all of the locations in which this movie took place, and that just helped inform our writing process as well; getting to be able to visualize the actual spaces. Add to that, we went to Stanford University to the Allen Ginsberg archives. It wasn’t about the lack of material out there. If anything, it was about making sure that we really just focused on who they were up until the point which the movie takes place.

Austin Bunn: Just to add to that, the people that I know that have seen the film have been really surprised at how much is actually totally accurate. The day after the murder, Allen Ginsberg went to the West End Bar, “You Always Hurt the One You Love” was playing on the jukebox and he wrote the poem that ends the film. It ends with “I am a poet;” that is a line from August 20, 1944 so we worked really hard to weave it in. But like John was saying before, we didn’t want to do the dutiful, stuffy, every box checked kind of biopic that has been around for a while. We wanted to do something that felt more in line with the spirit of the beats that was more specific and honest and transgressive, and I hope we got there.

Question: Did you two have a specific goal of what you wanted to portray and what you wanted the audience to leave with either of the time or of the characters themselves?

John Krokidas: What I want the audience to leave with is that feeling of when we were 18 and 19 years old just like these guys were in the movie; when everything seemed possible and you knew that you had something important to say about with your life. That you wanted to do something different and unique and not just what your parents taught you, not just what school taught you, but you wanted to really leave your mark on the world. The fact that after the movie these guys actually did it and created the greatest counterculture movement of the twentieth century is amazing. I have had plenty of people come up to me after seeing the movie and said, “This movie made me want to be a better writer” or “this movie made me want to go back and start playing music again.” That to me means everything. That’s ultimately, deep in my heart, why I wanted to make this movie.

Austin Bunn: The pivot point was this murder. I loved Allen Ginsberg for his openness and his honesty, and to think that at one point in his life he was called upon to defend his best friend in an honor slaying of a known homosexual, the very thing that Ginsberg went on in his life to defy and radically create change about the idea of being in the closet and the shame around that issue, that contradiction was really exciting to us dramatically.

John Krokidas: You know this movie took, from the time that we started talking about this until the time that we are getting the chance to be with you all today, over 10 years to make. When I really think about it, the thing that kept me going and kept me wanting to tell this story is that there needs to be something that pisses me off at night. The fact that in 1944 you could literally get away with murder by portraying your victim as a homosexual, that pissed me off to no end. This isn’t a political movie and it’s one scene and it’s obviously what informed how Lucien Carr got away with murder, but for me that was the thing that kept me up all night that said, “No, I have to tell the story.”

Question: The movie has different kinds of music playing throughout it like jazz and contemporary music. Did you envision using different musical styles when it came to making this movie?

John Krokidas: I originally wanted a bebop jazz score similar to Miles Davis’ score for Louis Malle’s “Elevator to the Gallows” because the transition from swing to bebop at this time was exactly what these guys wanted to do with words; to go from rhythms to exploding them into something beautiful. My music supervisor, Randal Poster, said to me, “John put down your academic treatise, put down your paper. Go make your movie. Your child’s going to start becoming the person that he or she wants to be.” So I went and I made my movie, and then I put jazz music on the film and it didn’t work at all. And then I went and did only period accurate music and it felt like Woody Allen’s “Radio Days” which is a great movie but it’s not the young rebellious movie about being 19 and wanting to change the world that we wanted to make. So, I actually went back to the playlists that Austin and I used a while writing this movie and I used Sigur Rós and stuff that was timeless but contemporary, and it brought the movie to life. Then I realized that the composer Nico Muhly had arranged all of those albums and worked with Grizzly Bear and Björk and other people that we were using as temp track. So, we got the movie to Nico and just thankfully he loved it. Now that I knew that I had contemporary music in a period film, then we get to that heist sequence. I had heist period music on it, it was so corny. The sequence didn’t work, it didn’t have any stakes to it, and I can academically tell you when the beats come on, they led to the hippies which led to the punks, and the punks led to Kurt Cobain and the 90s, etc. But the truth is that while I can intellectualize it, you go with what’s visceral and what feels honest and true to you. For me, the biggest lesson in making my first film is to do all of your homework, do all your research, know what you’re doing, but then don’t be afraid to get out of the way if your movie starts to tell you what you should be doing.

Question: How did you decide on what literary quotes to put in, and how did you work with the actors in establishing the cadence and the elocution on those?

Austin Bunn: What a great question! If you know any of the beat history, this new vision was real for them and they have written volumes about it, none of which makes any sense. We couldn’t make heads or tails of it.

John Krokidas: Do you all remember your journals when you were 20 years old or those conversations you had at three in the morning with other college students? We got to read their version of it, and there’s a reason that we hide all of our journals and don’t let them see the light of day.

Austin Bunn: It was challenging. With the uninhibited, uncensored expression of the soul, that’s actually a credible quote directly from the Ginsberg new vision manifesto. So in some ways we knew we had to distill some of that material from the Ginsberg journals to help make the argument for how valuable this manifesto was and the irony honestly of what transpires in the plot which is the very thing that Allen’s called to do which is to create this censored version of history. But in terms of the poetry itself, it was really challenging because as we all know there are movies about poets and writers where recitations happen and they are really flat and they can be corny and there’s a time where you tune out of the movie when you’re waiting for the poetry to end. Specifically, I think of Allen’s first poem that happens on the boat. We were really challenged to find a poem that would speak to audiences but was genuinely an Allen Ginsberg poem written in his voice. So what we had to do was really channel Allen. His early work is quite rough and burdened by trying to impress his dad and his professors. John had the concept of this isn’t a poem that he’s just reading to impress people, it’s a poem he’s reading to Lucien Carr. The audience knows that, you know that and Lucien finds it out on the boat at that moment. That really gave me permission to kind of rethink what the poem was going to do and how we would make it, so we came upon Allen’s method which was kind of magpie; stealing from the American vernacular and going out and finding common speech and repurposing it, creating this Whitman-esque inclusion. So you hear in the poem things that you’ve already heard in the film just like Ginsberg did himself. Things like Allen in wonderland is reworked in the poem, unbloomed stalwart is the very thing that David said to him at the party. So we’re kind of hopefully paying off not just a poem that is emotionally powerful, but also something of the method that Ginsberg would use for the rest of his life.

John Krokidas: Radcliffe was such a hard worker. While he was on Broadway doing a musical, we would meet once a week for two months before even preproduction and rehearsals began to work on the accent and to work together. I have him on my iPhone reading “Howl.” We didn’t look at the later recordings, we looked at the earliest vocal recordings possible of Allen Ginsberg to make sure that we weren’t capturing the voice of who he became, but his voice at that time and what his reading voice was like. To be honest, it’s just really telling the actor, “You’re not performing a poem. You are letting Lucien know that he is loved with this poem and that you love him and that you can see inside him.” It’s playing the emotion underneath the poem which was the direction.

Question: What does it do for you when all the main characters are gay? Normally you got the female characters who can be a love interest but they are not going to be a rival. Usually, even now in films and in life, there is a separate role where as if you are all the same gender, you can all be anything to each other.

John Krokidas: I think this is a movie with every character is discovering what their sexuality is (gay, straight, bi or all over the place), and more importantly whether or not they are worthy of being loved. I personally don’t know if Lucien Carr was straight or gay, and to me it’s irrelevant because I have seen this relationship play out amongst gay people I have known so many times where an older man who is gay and a younger man of questionable sexuality develops such a close bond. The stereotype I think would be is that the young man had an absent father figure or finds the older man’s confidence and just the care and nurturing qualities of them very attractive. What happens though is that those two get so intimate that ultimately there’s nowhere else to take the relationship but sexual, and when that happens then the power position in that relationship twists and the younger man suddenly realizes that he holds the power because he’s the sexually desired one. That’s where a lot of conflict ensues. Whatever you read about that relationship between Lucien and David, everyone knew that they were codependent. Everyone knew it was toxic and going to end badly. Nobody knew it was going to end in murder.

Austin Bunn: I think a lot of the biopics we see are kind of denatured of their sexual qualities and the edginess of the relationships in them. So, I think we were trying to do something that restored some of that ambiguity, lust, desire and confusion that is genuinely in the beats’ history. We were not making that up.

“Kill Your Darlings” is available to own and rent on DVD, Blu-ray and Digital.