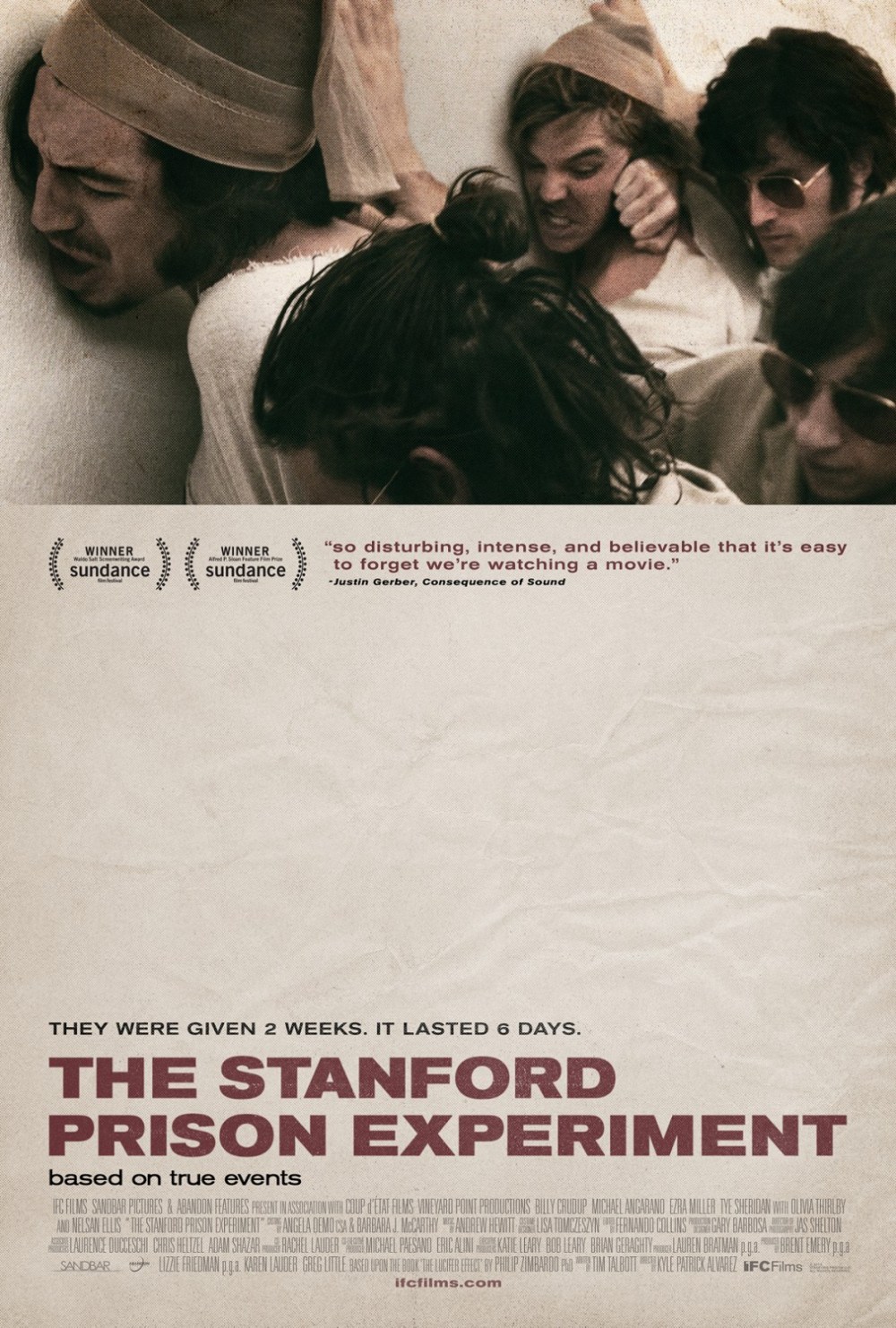

Exclusive Interview with Kyle Patrick Alvarez about ‘The Stanford Prison Experiment’

Kyle Patrick Alvarez’s “The Stanford Prison Experiment” takes us back to the year 1971 when psychology professor Philip Zimbardo (played in the movie by Billy Crudup) conducted the infamous experiment which had 24 students playing the roles of prisoners and guards in a makeshift prison located in the basement of the school’s psychology building. Things start off well, but the experiment soon goes out of control when the guards become increasingly abusive to the prisoners, and Zimbardo is unwilling to stop their brutality as he is infinitely curious to see what it will produce. Zimbardo was out to test his hypothesis of how the personality traits of prisoners and guards are the chief cause of abusive behavior between them. The experiment was supposed to last fourteen days, but it ended after 6.

What results is one of the most intense moviegoing experiences from the year 2015 as a cast of actors including Ezra Miller, Tye Sheridan, Michael Angarano, and Logan Miller find themselves caught up in the experiment’s grip to where the line between reality and fiction is completely blurred. Whereas previous films have observed this experiment from an academic standpoint, this one observes it from an emotional one.

I got to talk with Kyle while he was in Los Angeles to promote “The Stanford Prison Experiment.” His previous films as writer and director were “C.O.G.” in which a cocky young man travels to Oregon to work on an apple farm, and “Easier with Practice” which tells the tale of a novelist going on a road trip with his younger brother to promote his unpublished novel.

Ben Kenber: “The Stanford Prison Experiment” is one of the most movies you don’t watch as much as you experience.

Kyle Patrick Alvarez: I’m finding that out, yeah (laughs).

BK: There are only so many movies you can say that about. “Deliverance” is a good example of that.

KPA: I was really humbled. When the movie first played I think the first question at the Q&A was, “Did you feel like this movie was an experiment on the audience?” I was so taken aback by the question not in a negative way, but because no one had seen the movie before. I was actually working so hard to not overburden the audience with the story. We even tempered it down a lot. They were stripping guys by the end of day one. I think by the end it’s supposed to become burdensome to watch, and I embrace it now that that’s the reaction, but I didn’t know that that was going to be the case. So the first time the movie screened I was like. okay, it is playing this way to people and I know I can just embrace that now which is good. I hope not every movie I make is like that, but hopefully the movie earns it and then people appreciate the challenge of the experience of watching it.

BK: I remember hearing about this particular experiment while I was in a psychology class in college, and we even watched a documentary about it as well. The one thing that stood out to me the most was when the prisoners started saying “prisoner 819 did a bad thing,” and they kept saying it over and over. I kept waiting for that moment to come up in this movie.

KPA: Oh yeah. I felt like that was one of the really iconic things that you hear. You can hear it over and over and over again in your head, and I think we even joked at one point that they could release a teaser that was just that over and over again. That was interesting to me. As I read the script I had all these things that seemed larger than life, and when you read about it or saw the footage you’re like oh these things really did happen. The Frankenstein walk, to me, is so bizarre and so odd, yet it’s a real thing. To try to make a film that embodies that sort of spirit was hopefully the aim.

BK: This movie is “based on a true story,” but you didn’t use that phrase at the start of it. I was glad you didn’t because this phrase has long since lost its meaning.

KPA: I kind of fought for that a little bit actually. My whole argument was that marketing is going to say it no matter what. I’m a firm believer that you want the movie to stand on its own regardless of marketing, but at the same time I just don’t know anyone that would go to a movie called The Stanford Prison Experiment and not know anything about it and not know it was based on a true thing. I talked about it when I first got involved in the film that “based on a true story” means nothing anymore. The movie I was using for an example was the one where Eric Bana plays a cop who is hunting demons in New York City (“Deliver Us from Evil”), and the trailer says it was “based on a true story.” There are demons in New York; we know this as fact, right? There are not people who hunt demons in New York. Maybe there’s someone who said he does once, but that doesn’t mean it is based on a true story. So, it just doesn’t mean anything to people anymore and it doesn’t carry any weight or value. I tried to think of some other vernacular it could be. I didn’t want it to be like this is a true story because then that says everything in it is true, which is a lie. As soon as you make a movie on anything, nothing in it is true anymore.

BK: With movies based on real events there are dramatic liberties taken, but with this one it sounds like that wasn’t entirely the case.

KPA: I think we reduced the dramatic liberties quite a bit. I think if you look at a movie, for example, like “Lincoln” which takes voting public record and changes it. I don’t mean to slam the film, I like the film quite a bit, but when they’re voting they change the numbers to make it more suspenseful. I don’t think we took any liberties anywhere near that extreme. Maybe some people who were in the experiment could argue that it wasn’t really that intense or something like that. Others may argue that the intensity comes from putting the camera in their faces or the artistic representation of it. Two of our biggest liberties are when Ezra (Miller) and Brett (Davern) escape the prison. In real life the guy really did take a panel off. He was a guitar player and took the panel off with a sundial, broke the lock and I think they tried to open a door, but a guard was there and admonished them and told them that they had to fix the lock. We added an extra couple hundred feet. When we were doing that we said that we were gonna add this chase sequence because the movie needs to breathe and open up a bit. I thought Tim (Talbott) had done a really good job with that in the script. But then when Phil (Zimbardo) comes around and the other guys, there’s a reason we never see them touch them because they didn’t. That was where we were embellishing a little bit for the sake of the narrative, but we’re not abandoning the fundamentals of what this experiment was about. Those guys did not touch them or physically harass them so we didn’t show that, and having Phil involved was a really good and constant reminder of what those fundamentals are that we shouldn’t change. The ending, when they called it off, actually Phil and Christina kind of said that they needed to call this off and they came up with a plan to do it professionally. For me, you show that and there is an anti-climactic nature to that. I think the emotions are real and that they were being felt, and we just put them in at different times for the ending. I was really interested in making a film that could hold up. If you sit down and watch the documentary “Quiet Rage,” you will go oh, that is actually pretty similar. I didn’t want to make a movie that would replace that or replace “The Lucifer Effect.” I wanted to make a film that would work in tandem with those where it would feel like you could gain something a little more emotional and different than if you just did the academia side.

BK: The actors are all fantastic in the movie and they each give very intense performances. Watching them made me wonder if the movie was an experiment on them.

KPA: In a weird way, I almost wish I had this story to make interviews more exciting about these kids became their characters and I became like Zimbardo. But the truth was I think I was actually overtly aware of that potential, and actually it would have worked so hard against us. If you ask any of the guys, they will say that they had a lot of fun. You only have two options: either go down the path where everyone has fun and everyone gets along, or you gotta push it to go really extreme. I am not a big manipulator. If an actor wants me to manipulate them I will work with that, but on this film it was one of those things where it’s like when the camera’s rolling we’re on, and when it’s off be respectful. Some guys might need more space and might want to stay in character a little bit more, but it never took on the form of the experiment. We did spend two and a half weeks in that hallway, and we were sick of the hallway. We were ready to be done. Sure, some feelings were created, but I told them everyone every day that this is like a soccer game where we all shake hands at the end. So if something is going on that you’re not comfortable with, just say it. I said that probably more to the guards than the prisoners, but once it came down to doing those few physical things in the movie the actors loved it. Nick and Ezra had worked together before so they already respected each other, and they would just run through their scenes and had such a blast. For me, in a weird way we actually worked against that, and I think consequently the actors look back on it very fondly. I also think we got, for the nature of the movie and the tight shooting schedule, better stuff from them because they just felt more invigorated. I would just love to be able to build a career out of actors having good experiences. That’s my favorite party of the process, working with actors. I admire what they do so much because I never could, so it’s honoring that by working to each person. But this is the first time I ever did an ensemble piece and it was a little more about telling them hey this is what it’s going to be like, hey it’s not going to get out of control, guards you are going to follow the script and if you want to push something a little bit more than we’ll talk about it as opposed to unleashing them. There have been previous iterations of this project where that had been the aim where they try to create this potboiler environment where the actors really lose it, but I think what you get with that is more of a machismo quality. I jokingly refer to it as the David Ayer effect. I like his movies so it’s not a slam on them at all, but he’s making testosterone and there’s no doubt about it. I actually was more interested in making the inverse of that. The set was like a frat house, but the aggression was coming from a more complicated place. There wasn’t any actual physical violence. When you look closely at the movie there is no drop of blood other than one or two moments. No one was physically hurt, and so we were really careful to honor that while still creating tension.

BK: One interesting scene is when Ezra Miller’s character gets arrested as part of the experiment. He treats it like it’s no big deal at first, but then the cops slam his head on the car and his mood changes instantly.

KPA: They really did get real cops and they said arrest these guys like they are really criminals. This is something we didn’t have the money to shoot, but they actually took them to the police station and fingerprinted them and booked them and took photos of them and everything. They really put them through this simulation and it really got to them. The cops were really putting paper bags on their heads. Someone criticized the film once saying that they used too much on the nose imagery from Abu Ghraib, specifically referring to the bags. I was like no, no, no, Abu Ghraib just did the same exact thing.

BK: It seems like certain audience members need to be reminded that the Stanford Prison Experiment took place long before Abu Ghraib.

KPA: Oh yeah. It’s one of those stories that’s too bizarre to be true. It’s hard to accept that it was true. I knew there was no way to succeed 100% on this but I tried to work the hardest to make a film that didn’t just always say, “Well it really did happen.” That’s not enough of an answer when you make a movie like this because you have to make the audience feel like it could have happened. I wanted it to be like, “Well I understand why it happened.”

BK: By the time the movie gets to day three, it feels like we have been with these guys for a month.

KPA: Yeah (laughs), that’s how they felt too. They really did not know how many days had passed. They weren’t sleeping which I think was the biggest thing. You can go 36 hours without sleep when you start to legitimately lose your mind, and I think that’s a huge part of what happened.

BK: The Stanford Prison Experiment was supposed to last two weeks, but it ended up being shut down after 6 days. Some have said that it wasn’t because the experiment wasn’t successful, but that it was too successful. Would you say that was the case?

KPA: I think once you talk about success of the experiment you start to bring into the question its true purpose and its ethics. I was really interested in pushing questions of things like that in the movie. At the same time, I didn’t want to fall into the question of, was this okay? People are still arguing the exact same things, so I figured we are never going to solve this. 40 years later people are still arguing whether this experiment succeeded or not or whether it should have never have ever been done in the first place. What we do know now is that the experiment would never be allowed to happen today. It was military financed. Partly because of the experiment, there are so many more checks and balances in place. When I first sat down with Billy (Crudup), one of the things he said was, “How could everyone be so naïve to not realize this would happen?” And I said, “Well of course, they could have because it hadn’t happened yet.” Now it’s easier for us to go, “Well, of course, it would have gone wrong. What were they thinking?” They were doing experiments like this all the time; simulations or recreations. This was just part of what psychologists were doing at the time. This was the time it just really imploded.

BK: That’s a good point. Ever since then we have a better understanding of the power dynamic between prisoners and guards more than ever before.

KPA: Yeah, and that’s why I added a line at the end when Billy is talking to the camera. He says, “There was no sense of precedent. We didn’t know this was going to happen.” I thought that was a really important element.

I want to thank Kyle Patrick Alvarez for taking the time to talk to me. “The Stanford Prison Experiment” is now available to own and rent on DVD, Blu-ray, and Digital.