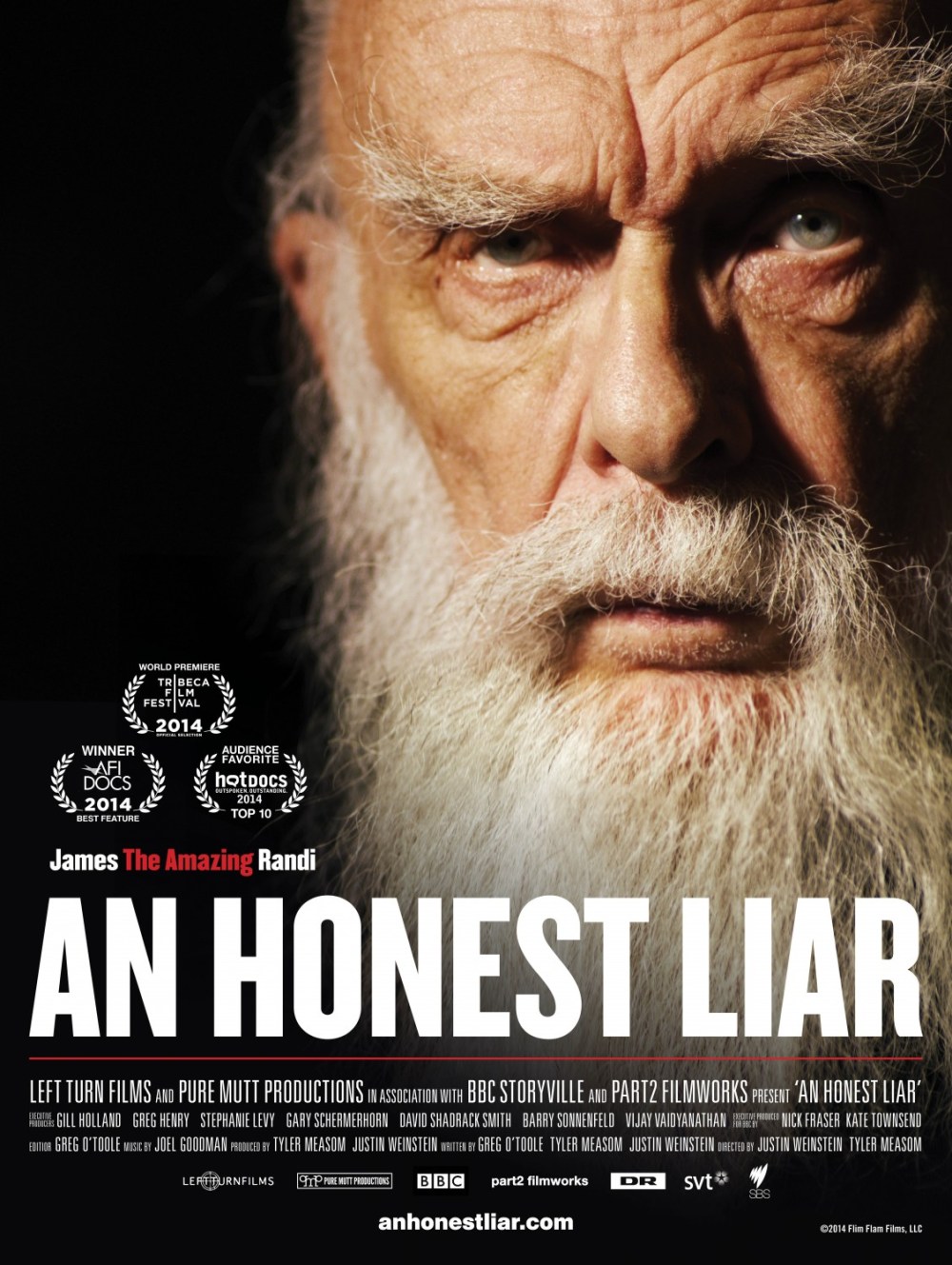

Exclusive Interview with Justin Weinstein on ‘An Honest Liar’

In 2015 there were many incredibly fascinating documentaries released, and one of them was Justin Weinstein’s and Tyler Measom’s “An Honest Liar.” It looks at James Randi, a world famous magician, escape artist and renowned enemy of deception. Randi started out his career as a stage magician with aspirations to be the next Houdini. After retiring he went on to publically expose famous psychics, faith healers and con artists who were deceiving people for their own benefit. But things take a shocking turn when it is revealed that Randi’s partner of 25 years is not all he appears to be, and it leaves the audience wondering if Randi is the deceiver or the deceived.

“An Honest Liar” is available to rent or own on Blu-ray and DVD, and it offers the documentary’s fans a treasure trove of special features to check out. There are two commentary tracks to listen to: one with the directors and the other with Randi himself. There’s more about Project Alpha, the elaborate hoax Randi orchestrated where two fake psychics were planted in a paranormal research project and who led others to believe they were for real. In addition, there are deleted scenes as well as extended interviews with Penn & Teller, Alice Cooper, Banachek and Ray Hyman.

I got to speak with one of the co-directors of “An Honest Liar,” Justin Weinstein, over the phone, and we had a great talk about this documentary’s making as well as the challenge of making any documentary in this day and age. Weinstein is a Brooklyn-based filmmaker who was the executive producer on “Bronx Obama,” and he was also a writer and editor on “Being Elmo: A Puppeteer’s Journey” which won the Special Jury Prize at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival.

Ben Kenber: How did “An Honest Liar” change from how you envisioned it before filming to what it eventually became in its finished form?

Justin Weinstein: That’s a great question. We originally started out thinking that the film would be as much about skepticism as it is about Randi. Before we even started filming we thought about what we can do here, and we were interested also in the skeptic movement because there is a very avid movement and active almost religious evangelical group of skeptics with their own charismatic leaders. So we thought that was interesting and our working title began with Skeptic. Of course we were going to deal with Randi’s history, but we were planning to look more at the contemporary skeptic movement as well. But then something happened Randi’s partner got arrested. In doing research and talking to people and going through Randi’s history, there were a lot of interesting disparities. He’s a storyteller and a performer, and when you’re a storyteller and a performer often the best stories are not exactly what happened. And so Randi has kind of bent the truth at times in order to be more effective at what he does, which ironically is being a truth teller (laughs). So we were starting to get interested in the levels of deception, truth, honesty, and a kind of inherent irony with the truth teller bending the facts. Once his partner was arrested, we realized that there is something else bigger thematically here. So we went back and watched Orson Welles’ “F is for Fake” and that really solidified our thinking about the film and that its subject is deception. Above all else that’s the through line. I mean it’s about Randi, but it’s really about truth and deception as well. I knew I wanted to play with the audience and have there be something deceptive in the nature of the film itself. Most people think that documentaries are the truth, and we all know that’s not really the case or rather that they’re one form of the truth. So all these things gelled and helped us focus the film in the direction that it ultimately took.

BK: One of the ad-lines for “An Honest Liar” is if James Randi is the deceiver or the one being deceived. We live in times right now where it feels like we are all being deceived in one way or another, so that’s an interesting way to look at it.

JW: Yeah, and it also working on a couple of levels because it’s not clear right away whether Randi was deceived by Deyvi/Jose, and there’s also a scene in the film where I apparently deceive Randi as a filmmaker. The film came out about the same time I think as “Merchants of Doubt” which is another film about deception actually. (The magician) Jamy Ian Swiss is in that as well. Deception is of fundamental importance in what, to me, forms a lot of the problems that we have today whether it’s political, self-deception or other people pretending something is true when it isn’t.

BK: “Merchants of Doubt” is another terrific documentary and almost as good as “An Honest Liar.” Doubt is a big thing now, and I have had some strong debates with people who are guided more by religion than actual facts.

JW: Well that’s what got Tyler and I interested in this to begin with. I was brought up a secular Jew and was always interested in science and film. When I went to college in Ohio, in my Freshman year I took a genetics class and people stood up and walked out and screamed at the professor, “You’re gonna go to hell for teaching this!” And I was like, “Huh? What?” I remember the first time where I actually spoke to people who believed that dinosaurs didn’t exist and that dinosaur fossils were a plot. I was like, “Wait a minute, what’s going on here?” I transferred to film school and went into doing documentaries, and a lot of my work has been around that subject. I worked on a Peter Jennings doc where I dealt with UFO believers, and it just really fascinates me how people can come to believe things that are demonstrably untrue or just hold onto faith in something for which there is no tangible evidence. Tyler, my co-director, was brought up a Mormon in Salt Lake City. He went on a mission and converted people to Mormonism before he realized that he was being duped and lied to, and he left the church. So that was definitely, as filmmakers, part of what we found fascinating about the subject and wanted to explore.

BK: One of “An Honest Liar’s” most interesting moments is when people start turning against Randi even after he has proven others to be fraudulent in their methods. It seems like many people would rather believe in the illusion rather than face up to reality.

JW: Yeah, I learned this early on when I was debating people in an academic space between creationists they know and evolutionists. At a certain point, and this was when I was 17 or 18, my professor pulled me aside and I said that I couldn’t understand it. There’s evidence. How can they not accept the evidence? What I came to understand was that people create a kind of bubble, a worldview that works for them. If you poke a hole in the bubble no matter small it is, then the whole thing will collapse. So it requires these mental gymnastics to keep the structure of that bubble intact. Over the years making this film people would come up to us, email us and offer us services. Somebody from Paramount Pictures would be like, “Come and finish your film here. I was a born again Christian and I was sucked into all of this, and then I saw one of Randi’s videos on You Tube and someone gave me a book of his and that opened my eyes and changed my life.” He’s had that effect on thousands and thousands of people and it’s always amazing to see how thankful people are. People travel for hours and days to meet him in person to thank him because he changed their lives. It’s really stunning. At the same time there is a whole population of people out there who don’t know him. He’s not the hugest star. He was famous in the 50’s and 60’s and then the 70’s and 80’s with Uri Geller. One of the things we were hoping to do with the film was also to show a fascinating and really important person people deserve to know more about.

BK: Many wonder why a biopic of Randi’s life has not been made, but it makes more sense to tell his story through a documentary because it seems to be a more honest way to introduce this “liar” to a public not familiar with him.

JW: It’s funny because a few of his stories have been stolen. There was a movie with Steve Martin about faith healing called “Leap of Faith,” and then there was something with Robert De Niro where they steal the whole “hello Petey can you hear me” (“Red Lights”), and that’s right out of Randi’s life. There have been other people who had approached him to make a documentary, but I don’t think any of them seemed right. I think both Tyler and I have some films under our belt and we are coming at it from the right angle, so he trusted us.

BK: How open was Randi to doing a documentary? Was he ever hesitant to go into certain areas of his life?

JW: He said at the very beginning, “If we’re going to do this, we’re going to do I warts and all,” and so he was very willing to be open. Right after his partner was arrested it was just unclear what would happen and what was happening. There was a little bit of caution, but as soon as things started coming out both he and his partner just decided that honesty is the best policy. He was very giving with his time. At one point he was upset and you see it in the film, but now he says that he’s glad that we included it because he wants people to see that even he sometimes grapples with the truth that we’re all human.

BK: You also managed to get an interview with Uri Geller which is amazing because he was one of Randi’s chief targets throughout the years. Was it tough getting an interview with Uri, and how open was he to talking with you?

JW: It’s funny. We sent him an email and said we were doing a documentary on Randi and that he has been a big part of Randi’s life and we would love to interview him. We got an email back from his lawyer saying, “Well my client has had a very contentious history with Randi and we want to know exactly how you are going to portray him and the questions you are going to ask.” And Tyler and I looked at each other and we were like, “Screw that!” I never write out a list of questions when I do interviews, I do it conversationally. We have enough of Geller in archive videos. We didn’t need him on camera. So we replied and said we don’t write questions, we got enough in the history to do it without him and he is open to speak for himself. So if he wants to do it great, if not no worries. And then the phone rang and it was Geller who was like, “Oh I’d love to!” So as soon as we threatened to pull the camera away, he ran toward it. Randi said the most dangerous place to be is between Uri Geller and a TV camera. He was very gracious, he was very nice and he was game.

BK: In regards to the Blu-ray/DVD release, what special features are you excited for the fans of the documentary to check out?

JW: There were so many great stories that we couldn’t fit in. With Project Alpha, the two magicians who infiltrated the paranormal study, that went on for two years and they were a couple of high school teenage boys who were away from home and getting into trouble. So there are a few stories from that we couldn’t fit in time wise to the film, but we kept them as bonus scenes. There are a few more Project Alpha tidbits, and the extended interviews are also really great. You can hear Penn and Teller, or rather just Penn, talk about his impressions of Randi because Randi is one of Penn’s biggest heroes. He is very articulate about why Randi deserves the praise that he gets and what is special about his life.

BK: Speaking of Project Alpha, Barry Sonnenfeld now has plans to make a movie about that. What are your thoughts on that?

JW: We’re thrilled. Barry saw the film and loved it, and he immediately recognized Project Alpha as its own great story. We met with him and agreed to work together. He’s a very talented filmmaker who started out as a cinematographer on the Coen brothers’ films but then did “Get Shorty” and “Men in Black.” He’s a great match for the material. It’s kind of a buddy, slightly supernatural period comedy-ish thing, so we’re thrilled to be working with him. We hope to get something up on the big screen with him.

BK: “An Honest Liar” was made with the help of Kickstarter and a lot of grassroots support. Could this documentary have been made without that grassroots support?

JW: That’s a good question. We raised a good amount of money via crowd funding, but our budget was much higher. The money we raised was not enough to make the film on its own by any means so it wouldn’t have been sufficient. However, without it, it would have been much more difficult and I’m not sure it would have been possible without it. In fact, most likely it would not have been possible without crowd funding unless we really cut a lot of corners, and it probably would have been a different film. Documentary funding is always hard to come by especially in the United States. In many other countries there are government funding programs, there’s state money, and in the United States there is no such thing. So you have to do a lot of work applying for grants, but mostly grants that are available tend to be for social issues and ideological films. They are subject oriented about underrepresented populations and minorities, so making a film like this, and it is an issue oriented film, it’s not the kind of issue that grant foundations like. It looks like a biography to most people, so we didn’t have those sources in funding available to us and it’s a shame. I think we made a decent film and I think a lot of foundations which had seen the film after it was made have said, “Oh, well that’s something we could have supported.” They prioritize their money, so crowd funding is almost essential to documentary filmmaking. It’s a shame. It really sucks.

I want to thank Justin Weinstein very much for taking the time to talk with me. Be sure to check out “An Honest Liar” on Blu-ray or DVD as those special features are every bit as entertaining as the documentary itself.

Copyright Ben Kenber 2015.